We have found some common guidelines that help us determine whether studies and websites can be trusted. We share what we find valuable in a series of blog posts. Andy Jackson, ND, and Miki Scheidel reviewed and provided input on this post.

This post is written with health professionals in mind. Other posts in this series are for a more general audience.

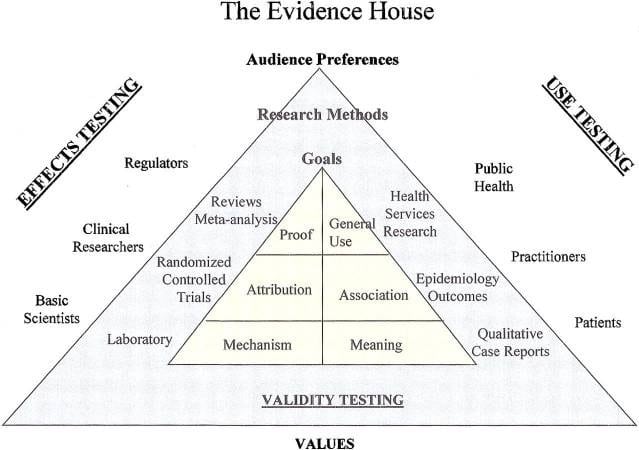

CancerChoices advisor and integrative physician Wayne Jonas, MD, explains that the strongest study designs don’t always provide the best evidence:1Jonas WB. The evidence house: how to build an inclusive base for complementary medicine. Western Journal of Medicine. 2001 Aug;175(2):79-80.

As most clinicians know, the reasons that patients recover from illness are complex and synergistic, and many cannot simply be isolated in controlled environments. The best evidence under these circumstances may be observational data from clinical practice that can estimate the likelihood of a patient’s recovery in a realistic context.

In addition, patient’s illnesses are complex physical, psychological, and social experiences that cannot be reduced to single, objective measures. In some cases, the most valuable information for a clinical decision is a highly subjective judgment about life quality. This personal experience of illness might be captured only through qualitative research, not using questionnaires or results of blood tests. The “best” evidence under these circumstances may be the meaning that patients give to their illness and recovery.

At other times, the “best” evidence comes from laboratory studies. The discovery that St John’s wort can reduce blood levels of immunosuppressive drugs, for example, is the most crucial evidence when making decisions about its use in patients taking immunosuppressive medications. Findings of controlled trials often do not reveal such drug interactions. Arranging types of evidence in a “hierarchy” obscures the fact that sometimes the best evidence is not objective, not additive, and not clinical.

Dr. Jonas has proposed an “evidence house” with different “rooms” and different “wings” for different audiences and purposes.

Rooms in one wing of the house contain types of scientific information such as laboratory research. These rooms seek to find causes of disease, how therapies work, and proof of effectiveness—types of information that can be difficult to determine or that may take many decades.

Another wing has rooms with information about therapies’ relevance and usefulness in clinical practice rather than absolute proof of effectiveness.

“If resources are disproportionately invested in certain rooms of the house to the neglect of others, it is not possible to obtain the evidence needed for full public participation in clinical decisions…Each has different functions and all need to be high quality.”2Jonas WB. The evidence house: how to build an inclusive base for complementary medicine. Western Journal of Medicine. 2001 Aug;175(2):79-80.

In conclusion, researchers may have a strong study design and get convincing evidence that isn’t especially relevant to actual people and clinical care. Interpreting study results involves assessing the trade-offs between highly controlled situations and relevance to real life, then using the evidence that makes the most sense in the situation.

Helpful link

Other posts in this series

References

Ms. Hepp is a researcher and communicator who has been writing and editing educational content on varied health topics for more than 20 years. She serves as lead researcher and writer for CancerChoices and also served as the first program manager. Her graduate work in research and cognitive psychology, her master’s degree in instructional design, and her certificate in web design have all guided her in writing and presenting information for a wide variety of audiences and uses. Nancy’s service as faculty development coordinator in the Department of Family Medicine at Wright State University also provided experience in medical research, plus insights into medical education and medical care from the professional’s perspective.