This guide explains how pain affects your well-being during and after cancer treatment, and what you can do to manage it. Topics covered:

- Overview of pain, including common causes and types of pain

- Top evidence-based practices and therapies to manage pain

Pain at a glance

Between 50% and 70% of people with cancer report pain during cancer treatment, as well as about 65% of people with advanced disease.1Pujol LA, Monti DA. Managing cancer pain with nonpharmacologic and complementary therapies. Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 2007 Dec;107(12 Suppl 7):ES15-21; van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, de Rijke JM et al. Prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: a systematic review of the past 40 years. Annals of Oncology. 2007 Sep;18(9):1437-49. Controlling pain needs to be a priority.

Keep in mind three important facts about cancer-related pain:

- Not all types of cancer or cancer treatments are linked with pain.

- Cancer-related pain can be managed, often with therapies that are very simple to use.

- Experts can help you if you are experiencing pain.

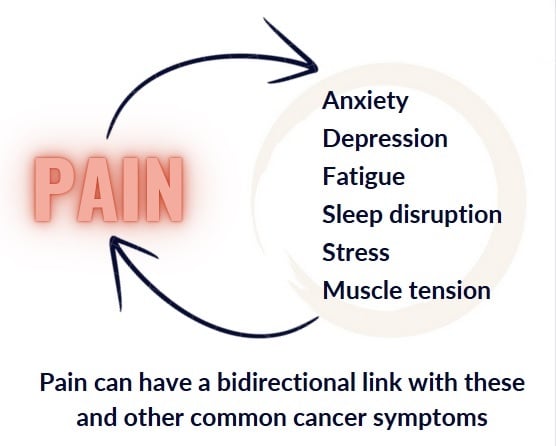

Uncontrolled pain greatly reduces your quality of life, wearing you down and making other issues seem worse. Pain may contribute to imbalances in body terrain › linked to cancer growth, such as changes in stress hormones and increased inflammation. Pain can also lead to worse cancer-related symptoms, such as depression, anxiety, sleep disturbance, and distress. People whose persistent cancer-related pain is controlled may even live longer than those with uncontrolled pain.2Zylla D, Steele G, Gupta P. A systematic review of the impact of pain on overall survival in patients with cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2017 May;25(5):1687-1698; Quinten C, Coens C et al; EORTC Clinical Groups. Baseline quality of life as a prognostic indicator of survival: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from EORTC clinical trials. Lancet Oncology. 2009 Sep;10(9):865-71; Efficace F, Bottomley A et al; EORTC Lung Cancer Group and Quality of Life Unit. Is a patient’s self-reported health-related quality of life a prognostic factor for survival in non-small-cell lung cancer patients? A multivariate analysis of prognostic factors of EORTC study 08975. Annals of Oncology. 2006 Nov;17(11):1698-704; Zheng J, He J et al. The impact of pain and opioids use on survival in cancer patients: results from a population-based cohort study and a meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020 Feb;99(9):e19306; de la O Murillo A, Torres AC et al. Association of pain with the presence of additional supportive care (SC) needs in patients with advanced cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2022 Jun 1;40(16_suppl):e24071-e24071.

Controlling cancer-related pain is both a science and an art. Seek professional help if needed. Specialists in cancer care are trained either to help you manage your pain or to refer you to pain experts, such as palliative care specialists. Help is available, and the first step is reporting your pain to your doctor. While addiction to opioids is a concern, it can often be prevented by following directions and getting medical supervision.

We strongly encourage you to let your doctor know as soon as possible if you are having moderate or severe pain that is not being managed well with the medications and therapies you have been using. No one who cares about you wants you to suffer, alone and in silence. In fact, loneliness and lack of social support might make pain worse.3Pole L, Hepp N. How can Sharing Love and Support help you? What the research says. CancerChoices. February 10, 2024. So speak out, reach out, and let others be with you in and through your pain. Their presence with you is where comfort begins.

Pain: overview

What is pain?

One of the most important actions you can take to get your pain under control is telling your care team you have pain and describing where the pain is, how long it lasts, and what the pain feels like. These all influence how they treat your pain. Here are some terms that will help you and your cancer team understand your pain:

Reporting and describing your pain

Types of pain based on duration and timing

- Acute pain is short-term and usually ends after the source of the pain is addressed and the painful area heals, for example, pain related to a surgical incision.

- Chronic intermittent pain is longer term but not constant or nearly constant, such as waking up daily with joint pain that goes away with movement.

- Chronic persistent pain is present frequently or constantly throughout the day and persists beyond the time when a painful area is expected to heal.4Chronic Pain. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Viewed July 24, 2024. With persistent pain, the cause of the pain may not be resolvable. Many people with cancer fear that they will have persistent, intense pain, but such pain is not common except perhaps with advanced cancer.

- Incident pain is additional pain on top of the persistent pain and is caused by something you do or is done to you, such as a painful procedure or pain while riding in the car to treatments. If you have this type of pain, a short-acting pain medication and/or other therapy before the incident occurs could be helpful. Additional therapies may include using imagery or breathwork or acupressure before and during a brief, mildly painful procedure.

Keep a record and tell your care team about the timing of the pain—when it happens, how long it lasts, and how long pain management measures last. If you describe persistent pain, for example, the key is to use medications, therapies, and practices on a regular schedule to bring pain down to a manageable level and keep it there. This might mean, for example, getting acupuncture on a regular basis, taking long-acting pain medications, or using your TENS unit routinely throughout the day.

Types of pain based on location and cause

Showing where you are feeling pain and telling what it feels like is important for your medical team to correctly diagnose and treat it. If you have pain from cancer in a bone, for example, you will usually be able to point to it. This type of local pain can usually be relieved with targeted local treatment such as radiation therapy or anti-inflammatory drugs that reduce swelling around the tumor.

- Nociceptive pain is the most common type of pain among people with cancer, caused when body tissues are damaged.5Franks I. Nociceptive Pain. Healthline. January 28, 2024. Viewed July 23, 2024. There are two types of nociceptive pain:

- Somatic pain occurs in a local area, such as bones, muscle, or skin, and may feel sharp or like aching, cramping, gnawing, or throbbing.

- Visceral pain is in internal organs and tissues and feels vague and diffuse, sometimes radiating to other areas such as your back, chest, jaw, or arms. This pain is often described as squeezing, dull aching, moving, twising, colicky, deep, or pressing.

- Neuropathic pain is linked to nerve damage due to the cancer and/or treatments such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or surgery. With neuropathic pain, a tumor can be directly invading or pressing on nerves, or nerves can be injured by toxicity from chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Symptoms of high sensitivity (burning, tingling, electrical feeling) and symptoms of low sensitivity (numbness and muscle weakness) are both common with neuropathic pain.6Yoon SY, Oh J. Neuropathic cancer pain: prevalence, pathophysiology, and management. Korean Journal of Internal Medicine. 2018 Nov;33(6):1058-1069. For more information on managing this type of pain, see Neuropathy and other Neurological Symptoms ›

In sum, different approaches are used to manage acute, persistent, and incident pain as well as nociceptive and neuropathic pain. Palliative care is one of the most useful approaches for managing persistent pain. Read more about Palliative Care in Cancer ›

What can cause or trigger pain?

Pain is usually caused by tissue damage or nerve damage. Psychological status can also contribute to pain, such as with pain caused by nerve damage that becomes interconnected with fear, depression, stress, or anxiety.7Saling J. Pain Classifications and Causes: Nerve Pain, Muscle Pain, and More. Web MD. January 12, 2023. Viewed July 17, 2024.

Medical conditions

- Injury and inflammation: Injury is a common cause of pain. Pain can also be caused by inflammation, whether brought on by direct injury or not.8Totsch SK, Waite ME, Sorge RE. Dietary influence on pain via the immune system. Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science. 2015;131:435-69; Crane TE, Miller A, Skiba MB, Donzella S, Thomson CA. Association of chronotype and pain at baseline in ovarian cancer survivors participating in a lifestyle intervention (NRG/GOG 0225). Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2020;38(suppl) abstr 6018).

- Stress response: “A prolonged or exaggerated stress response may perpetuate cortisol dysfunction, widespread inflammation, and pain.”9Hannibal KE, Bishop MD. Chronic stress, cortisol dysfunction, and pain: a psychoneuroendocrine rationale for stress management in pain rehabilitation. Physical Therapy. 2014 Dec;94(12):1816-25.

- Hormone imbalances: Hormone imbalances or deficiencies can contribute to pain and can serve as biomarkers for the presence of severe pain.10Tennant F. Hormone testing and replacement in pain patients made simple. Practical Pain Management. 2012;12(6); Tennant F. The physiologic effects of pain on the endocrine system. Pain and Therapy. 2013 Dec;2(2):75-86. Example: lower estrogen levels among premenopausal women is linked to increased pain and an increased risk of developing chronic pain due to impairment of pain pathways.11Henry NL, Conlon A et al. Effect of estrogen depletion on pain sensitivity in aromatase inhibitor-treated women with early-stage breast cancer. Journal of Pain. 2014 May;15(5):468-75.

- Depression: The relationship between pain and depression works in both directions—each can trigger and impact the other.12Theobald DE. Cancer pain, fatigue, distress, and insomnia in cancer patients. Clinical Cornerstone. 2004;6 Suppl 1D:S15-21.

Medications and therapies

Conventional cancer treatments—chemotherapy, hormone therapy, radiation therapy, or surgery—can cause pain syndromes. For example, hormonal cancer treatments such as aromatase inhibitors are linked to joint pain.13Gragnolati AB. 9 Medications That Cause Joint and Muscle Pain. GoodRx Health. April 1, 2024. Viewed July 19, 2024; Paice JA, Portenoy R. Management of chronic pain in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2016 Sep 20;34(27):3325-45.

In addition to cancer treatments, other medications can cause pain or interfere with your pain treatment. For example, bisphosphonates which are prescribed for osteoporosis are linked to jaw and joint pain, and low-dose naltrexone will interfere with opioids. Consult your practitioner or pharmacist to see if any medications are contributing to your pain and to develop a plan to manage treatment-related pain.

Connections to cancer survival

Controlling cancer-related pain is linked to better survival,14Quinten C, Coens C et al; EORTC Clinical Groups. Baseline quality of life as a prognostic indicator of survival: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from EORTC clinical trials. Lancet Oncology. 2009 Sep;10(9):865-71; Zheng J, He J et al. The impact of pain and opioids use on survival in cancer patients: results from a population-based cohort study and a meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020 Feb;99(9):e19306; de la O Murillo A, Torres AC et al. Association of pain with the presence of additional supportive care (SC) needs in patients with advanced cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2022 Jun 1;40(16_suppl):e24071-e24071; Efficace F, Bottomley A et al; EORTC Lung Cancer Group and Quality of Life Unit. Is a patient’s self-reported health-related quality of life a prognostic factor for survival in non-small-cell lung cancer patients? A multivariate analysis of prognostic factors of EORTC study 08975. Annals of Oncology. 2006 Nov;17(11):1698-704. as in advanced prostate cancer, for example.15Zylla D, Steele G, Gupta P. A systematic review of the impact of pain on overall survival in patients with cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2017 May;25(5):1687-1698. People reporting pain with newly diagnosed metastatic solid tumors have shown a worse life expectancy than people not reporting pain.16de la O Murillo A, Torres AC et al. Association of pain with the presence of additional supportive care (SC) needs in patients with advanced cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2022 Jun 1;40(16_suppl):e24071-e24071. Because pain, advanced cancer, and pain medications each contribute to worse survival, we can’t conclude that reducing pain can by itself lead to better survival, but communicating pain and other symptoms to your cancer care team may lead to better survival among people with cancer.17Basch E, Deal AM et al. Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA. 2017 Jul 11;318(2):197-198. Reducing pain will certainly improve quality of life for anyone with advanced cancer.

Top evidence-based practices and therapies for managing pain

If your pain is a symptom of other medical conditions such as those mentioned above, you may need to treat the underlying condition to address the cause of your pain.

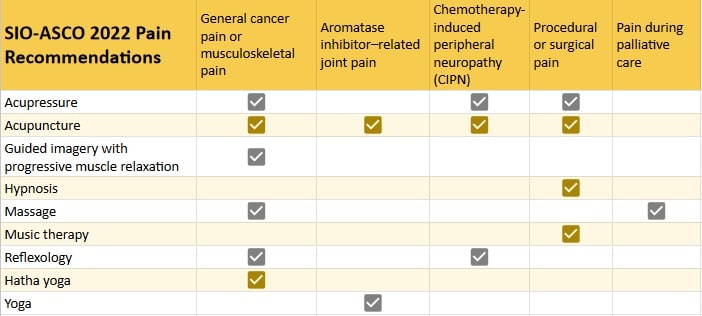

SIO-ASCO clinical practice guideline recommendations

In 2022, the Society for Integrative Oncology and the American Society of Clinical Oncology published Integrative Medicine for Pain Management in Oncology: Society for Integrative Oncology-ASCO Guideline ›

These recommendations are based on a rigorous review of complementaryin cancer care, complementary care involves the use of therapies intended to enhance or add to standard conventional treatments; examples include supplements, mind-body approaches such as yoga or psychosocialtherapy, and acupuncture therapies with a high level of evidence. Most of these therapies are also recommended in other clinical practice guidelines for managing cancer-related pain.18NCCN Guidelines for Patients ® Survivorship Care for Cancer-Related Late and Long-Term Effects. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2024. Viewed July 2, 2024; Ge L, Wang Q et al; International Trustworthy Traditional Chinese Medicine Recommendations (TCM Recs) Working Group. Acupuncture for cancer pain: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline. Chinese Medicine. 2022 Jan 5;17(1):8; Lam WC, Zhong L et al. Hong Kong Chinese medicine clinical practice guideline for cancer palliative care: pain, constipation, and insomnia. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2019 Jan 22;2019:1038206; Ling CQ, Fan J et al; Chinese Integrative Therapy of Primary Liver Cancer Working Group. Clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of primary liver cancer with integrative traditional Chinese and Western medicine. Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2018 Jul;16(4):236-248; Greenlee H, DuPont-Reyes MJ et al. Clinical practice guidelines on the evidence-based use of integrative therapies during and after breast cancer treatment. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2017 May 6;67(3):194-232 (this set of guidelines has been endorsed by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO): Lyman GH, Greenlee H et al. Integrative therapies during and after breast cancer treatment: ASCO endorsement of the SIO clinical practice guideline. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2018 Sep 1;36(25):2647-2655); Paice JA, Portenoy R et al. Management of chronic pain in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2016 Sep 20;34(27):3325-45; Deng GE, Rausch SM et al. Complementary therapies and integrative medicine in lung cancer: diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013 May;143(5 Suppl):e420S-e436S; Deng GE, Frenkel M et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for integrative oncology: complementary therapies and botanicals. Journal of the Society for Integrative Oncology. 2009 Summer;7(3):85-120.

Download the SIO and CancerChoices Integrative Oncology eBook ›

Different therapies are recommended for different types of pain, as shown in this table.

- Acupressure is the application of pressure to specific places on your body. See Acupressure: affordability and access ›

- Acupuncture is a practice of inserting fine needles into the body at specific points. It is recommended in other guidelines. See Acupuncture: affordability and access ›

- Guided imagery with progressive muscle relaxation uses imagination of something calming (imagery) and refocusing your attention and increasing awareness of your body (relaxation). See Guided Imagery: affordability and access › and Relaxation Techniques: affordability and access ›

- Hypnosis or hypnotherapy is a technique to induce a state of greater awareness, focused attention, and deep relaxation to manage symptoms or help a person gain control over behaviors they’d like to change. Learn more about hypnotherapy for cancer ›

- Massage manipulates soft tissues in the body. Find an oncology massage practitioner ›

- Music therapy uses music interventions within a therapeutic relationship. Learn more about music therapy ›

- Reflexology uses gentle pressure on specific points along feet, hands, or ears. Find a practitioner at the Complementary and Natural Healthcare Council › or American Reflexology Certification Board ›

- Yoga is a mind-body practice that includes breath control, meditation, and physical postures. Hatha yoga is one of many types of yoga. See Yoga: affordability and access ›

Other practices and therapies

Conventional therapies

Various prescription drugs may help manage pain. Ask your doctor for recommendations, but also ask about side effects from their use. Many of the lifestyle practices and complementary therapies described on this page have fewer side effects than prescription drugs.

- Opioids: In light of both benefits and risks of opioidschemicals that interact with opioid receptors on nerve cells in the body and brain to reduce the intensity of pain signals and feelings of pain. This class of drugs includes natural, synthetic, or semi-synthetic drugs such as oxycodone, hydrocodone, codeine, morphine, heroin, fentanyl, and many others.—including evidence of worse cancer survival19Budd K. Pain, the immune system, and opioimmunotoxicity. Reviews in Analgesia. 2004;8(1): 1-10.—integrative experts recommend they be used when necessary but in the smallest effective amount and, in the case of acute pain, for the shortest period possible. We encourage you to discuss opioid and non-opioid options such as ibuprofen (Motrin or Advil) or acetaminophen (Tylenol) with your healthcare practitioners to assess their use and safety.

- Physical therapy and/or cold and heat are recommended to help manage some types of pain. Conventional treatments for skeletal pain might include a back brace or limited bed rest for acute vertebral compression, surgery, and radiofrequency ablationuse of heat to destroy tissue pressing on nerves. Heat and cold are used to manage musculoskeletal pain, and cold packs on hands and feet are also used to reduce neuropathic pain during some types of chemotherapy.20NCCN Guidelines for Patients ® Survivorship Care for Cancer-Related Late and Long-Term Effects. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2024. Viewed July 2, 2024.

- Laxatives, enemas, and/or lots of fluids may be used to manage chronic pelvic pain.21NCCN Guidelines for Patients ® Survivorship Care for Cancer-Related Late and Long-Term Effects. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2024. Viewed July 2, 2024.

Lifestyle practices

We present practices backed by modestsignificant effects in at least three small but well-designed randomized controlled trials (RCTs), or one or more well-designed, mid-sized clinical studies of reasonably good quality (RCTs or observational studies), or several small studies aggregated into a meta-analysis (this is the CancerChoices definition; other researchers and studies may define this differently), goodsignificant effects in one large or several mid-sized and well-designed clinical studies (randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with an appropriate placebo or other strong comparison control or observational studies that control for confounds) (this is the CancerChoices definition; other researchers and studies may define this differently), or strongconsistent, significant effects in several large (or at least one very large) well designed clinical studies or at least two meta-analyses of clinical studies of moderate or better quality (or one large meta-analysis) finding similar results (this is the CancerChoices definition; other researchers and studies may define this differently) evidence of effectiveness.

- Losing excess weight can reduce musculoskeletal pain.22Hepp N, Pole L. Why is managing body weight important? CancerChoices. May 21, 2024. See What practices and therapies can help you manage your body weight? ›

- Stop smoking: People who avoid smoking have shown less pain from radiation treatment or surgery.23Baker S, Fairchild A. Radiation-induced esophagitis in lung cancer. Lung Cancer (Auckland). 2016 Oct 13;7:119-127; Kim DH, Park JY et al. Smoking may increase postoperative opioid consumption in patients who underwent distal gastrectomy with gastroduodenostomy for early stomach cancer: a retrospective analysis. Clinical Journal of Pain. 2017 Oct;33(10):905-911. See Healthy Lifestyle ›

Complementary therapies

We present additional therapies for reducing pain backed by modestsignificant effects in at least three small but well-designed randomized controlled trials (RCTs), or one or more well-designed, mid-sized clinical studies of reasonably good quality (RCTs or observational studies), or several small studies aggregated into a meta-analysis (this is the CancerChoices definition; other researchers and studies may define this differently), goodsignificant effects in one large or several mid-sized and well-designed clinical studies (randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with an appropriate placebo or other strong comparison control or observational studies that control for confounds) (this is the CancerChoices definition; other researchers and studies may define this differently), or strongconsistent, significant effects in several large (or at least one very large) well designed clinical studies or at least two meta-analyses of clinical studies of moderate or better quality (or one large meta-analysis) finding similar results (this is the CancerChoices definition; other researchers and studies may define this differently) evidence of effectiveness.

For guidance in selecting and using complementary therapies, see Finding Integrative Oncologists and Other Practitioners ›

Supplements and natural products

- Cannabis and cannabinoids are the buds or extracts from cannabis (marijuana) plants. People treated with either cannabis or some cannabinoids have shown less cancer-related pain.24Hepp N, Pole L. How can cannabis and cannabinoids help you? What the research says. CancerChoices. May 10, 2024. See Cannabis and Cannabinoids: affordability and access ›

- Topical (external) therapy using traditional Chinese herbal medicines such as Chanwu powder, Chanwu cataplasma, and modified Jinhuang powder/paste are recommended in clinical practice guidelines for managing cancer-related pain.25Lam WC, Zhong L et al. Hong Kong Chinese medicine clinical practice guideline for cancer palliative care: pain, constipation, and insomnia. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2019 Jan 22;2019:1038206; Ling CQ, Fan J et al. Chinese Integrative Therapy of Primary Liver Cancer Working Group. Clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of primary liver cancer with integrative traditional Chinese and Western medicine. Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2018 Jul;16(4):236-248. See Traditional medicine and professionals ›

- Intravenous vitamin C administered during or after cancer treatment may lead to less pain.26Hepp N, Pole L. How can intravenous vitamin C help you? What the research says. CancerChoices.April 12, 2024. See Vitamin C: Intravenous Use: affordability and access ›

- Melatonin is a hormone and supplement that regulates sleep cycles. People treated with melatonin around the time of surgery report less pain,27Hepp N. How can melatonin help you? What the research says. CancerChoices. July 3, 2024. although note cautions regarding how melatonin can interact with anesthesia.28Hepp N. Melatonin: safety and precautions. CancerChoices. July 3, 2024. See Melatonin: affordability and access ›

- Vitamin D supplementation may lead to lower pain during hormone therapy, and especially among people starting with lower vitamin D levels. People without cancer with low vitamin D levels requested less pain medication when treated with vitamin D in a large study, and another study found that postmenopausal women with low vitamin D levels reported more joint pain29Hepp N. How can vitamin D help you? What the research says. CancerChoices. January 14, 2025. See Vitamin D: affordability and access ›

Other complementary therapies

- Aquatic therapy involves treatments and exercises performed in water and may reduce certain types of pain, such as hormone therapy-induced arthralgia.30Cantarero-Villanueva I, Fernández-Lao C et al. Aquatic exercise in a chest-high pool for hormone therapy-induced arthralgia in breast cancer survivors: a pragmatic controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2013 Feb;27(2):123-32. It is recommended in practice guidelines.31NCCN Guidelines for Patients ® Survivorship Care for Cancer-Related Late and Long-Term Effects. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2024. Viewed July 2, 2024.

- Energy therapies effective for managing fatigue include biofield energy therapies or subtle energy therapies using touch, stimulation, or non-touch energy from a therapist. People treated with Reiki report less pain related to surgery.32Pole L, Hepp N. How can Reiki help you? What the research says. CancerChoices. November 25, 2024. Such energy therapies are recommended in practice guidelines.33Greenlee H, DuPont-Reyes MJ et al. Clinical practice guidelines on the evidence-based use of integrative therapies during and after breast cancer treatment. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2017 May 6;67(3):194-232 (this set of guidelines has been endorsed by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO): Lyman GH, Greenlee H et al. Integrative therapies during and after breast cancer treatment: ASCO endorsement of the SIO clinical practice guideline. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2018 Sep 1;36(25):2647-2655); Deng GE, Frenkel M et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for integrative oncology: complementary therapies and botanicals. Journal of the Society for Integrative Oncology. 2009 Summer;7(3):85-120. See pages on affordability and access for these therapies: Therapeutic Touch® ›, Healing Touch ›, Reiki ›, or Polarity Therapy ›

- Hyperthermia (heat treatment) during chemotherapy or radiotherapy may lead to less cancer treatment-related pain.34Hepp N, Jackson A. How can hyperthermia help you? What the research says. CancerChoices. April 11, 2024. See Hyperthermia: affordability and access ›

- Listening to nature-based sounds may lead to less pain.35Hepp N, Williams M. How can time in nature help you? What the research says. CancerChoices. December 21, 2023. See Time in Nature: affordability and access ›

- Meditation uses a technique such as focusing the mind to train attention and awareness. People practicing meditation may experience less pain during cancer treatment or procedures.36Soo MS, Jarosz JA et al. Imaging-guided core-needle breast biopsy: impact of meditation and music interventions on patient anxiety, pain, and fatigue. Journal of the American College of Radiology. 2016 May;13(5):526-34; Ahmed M, Modak S, Sequeira S. Acute pain relief after Mantram meditation in children with neuroblastoma undergoing anti-GD2 monoclonal antibody therapy. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology. 2014 Mar;36(2):152-5. Meditation is recommended in practice guidelines.37Deng GE, Frenkel M et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for integrative oncology: complementary therapies and botanicals. Journal of the Society for Integrative Oncology. 2009 Summer;7(3):85-120. Learn more about meditation ›

- Mindfulness such as mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) promotes relaxation and stress reduction through practices like meditation › and deep breathing. Mindfulness therapies are recommended in practice guidelines for managing cancer-related pain.38Paice JA, Portenoy R et al. Management of chronic pain in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2016 Sep 20;34(27):3325-45. Find mindfulness practices for people with cancer ›

- Mirror therapy may relieve chronic “phantom limb” pain after amputation39Chong DST, Pople M et al. Mirror therapy for the management of phantom limb pain: a single- center experience. Annals of Vascular Surgery. 2023 Sep;95:184-187; Purushothaman S, Kundra P, Senthilnathan M, Sistla SC, Kumar S. Assessment of efficiency of mirror therapy in preventing phantom limb pain in patients undergoing below-knee amputation surgery-a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Anesthesiology. 2023 Jun;37(3):387-393; Campo-Prieto P, Rodríguez-Fuentes G. Effectiveness of mirror therapy in phantom limb pain: a literature review. Neurologia (Engl Ed). 2022 Oct;37(8):668-681. and is recommended in practice guidelines.40NCCN Guidelines for Patients ® Survivorship Care for Cancer-Related Late and Long-Term Effects. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2024. Viewed July 2, 2024.

- Psychosocial therapies include cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), behavioral treatment, cognitive-behavioral stress management, support groups, and supportive/expressive therapy. They are designed to change negative thought patterns and behaviors or provide emotional support to improve emotional and physical well-being.41Mayo Clinic Staff. Cognitive behavioral therapy. Mayo Clinic. Viewed June 4, 2024. CBT, supportive/expressive therapy, and psychosocial support are recommended in practice guidelines.42NCCN Guidelines for Patients ® Survivorship Care for Cancer-Related Late and Long-Term Effects. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2024. Viewed July 2, 2024; Deng GE, Frenkel M et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for integrative oncology: complementary therapies and botanicals. Journal of the Society for Integrative Oncology. 2009 Summer;7(3):85-120. Learn more about CBT and find a practitioner ›

- Tai chi and qigong are forms of mind-body exercise and meditation. They show the most effectiveness in managing pain after cancer treatment has ended43Hepp N. How can tai chi or qigong help you? What the research says. CancerChoices. May 29, 2024. and are recommended in one practice guidelines.44Deng GE, Frenkel M et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for integrative oncology: complementary therapies and botanicals. Journal of the Society for Integrative Oncology. 2009 Summer;7(3):85-120. See Tai Chi or Qigong: affordability and access ›

- Therapies based on electrical stimulation include peripheral nerve stimulation, spinal cord stimulation, transcranial stimulation, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), and scrambler therapy. These can be effective in controlling some types of pain, such as neuropathic pain.45Smith TJ, Wang EJ, Loprinzi CL. Cutaneous electroanalgesia for relief of chronic and neuropathic pain. New England Journal of Medicine. 2023 Jul 13;389(2):158-164. One or more of these therapies are recommended for managing chronic cancer-related pain in guidelines.46NCCN Guidelines for Patients ® Survivorship Care for Cancer-Related Late and Long-Term Effects. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2024. Viewed July 2, 2024; Paice JA, Portenoy R et al. Management of chronic pain in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2016 Sep 20;34(27):3325-45. Learn more about these therapies ›

- Ultrasonic stimulation delivers pulsed ultrasonic waves to specific areas of the brain and can alleviate some types of pain.47Aiyer R, Noori SA et al. Therapeutic ultrasound for chronic pain management in joints: a systematic review. Pain Medicine. 2020 Nov 7;21(7):1437-1448; Petterson S, Plancher K, Klyve D, Draper D, Ortiz R. Low-intensity continuous ultrasound for the symptomatic treatment of upper shoulder and neck pain: a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Journal of Pain Research. 2020 Jun 2;13:1277-1287. It is recommended in one practice guideline.48NCCN Guidelines for Patients ® Survivorship Care for Cancer-Related Late and Long-Term Effects. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2024. Viewed July 2, 2024. Learn more about ultrasound therapy ›

Healing stories

Helpful links

General

National Cancer Institute: Cancer Pain Control ›

Body of Wonder podcast: Mind-Body Approaches to Understanding and Healing Chronic Pain with Howard Schubiner, MS ›

Roshi Joan Halifax, PhD: Meditations on Transforming the Suffering of Pain ›

Tracking and reporting pain

Spine and Pain Clinics of North America: What is a Pain Diary and How Can It Help You Relieve Pain? ›

For caregivers

Videos

Meditation and Cancer Pain

Thomas Smith, MD, Professor of Oncology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and Director of Palliative Medicine, Johns Hopkins Medicine, discusses the role of meditation in supporting people living with cancer pain.

Play videoManaging Anxiety and Depression during Cancer Pain

Thomas Smith, MD, Professor of Oncology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and Director of Palliative Medicine, Johns Hopkins Medicine, discusses the importance of screening for anxiety and depression in people experiencing cancer pain and how to help patients manage these conditions.

Play videoFor healthcare professionals

Basic principles of managing persistent cancer pain

Oncologists and palliative medicine practitioners usually consider widely accepted management principles in developing a treatment plan for persistent pain.49Paice JA, Portenoy R et al. Management of chronic pain in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2016 Sep 20;34(27):3325-45; WHO Guidelines for the pharmacological and radiotherapeutic management of cancer pain in adults and adolescents. World Health Organization. January 2019. Viewed January 27, 2023. “Communicating an intent to control pain and stress early on and emphasizing the concern reassures both the patient and family. This includes active, concerned inquiry about pain, sleep, mental status, energy, and functional capability. Discussion should include family members as well as the patient.”50Chapman CR, Gavrin J. Suffering and its relationship to pain. Journal of Palliative Care. 1993;9(2):5-13.

To learn more about basic principles for managing persistent pain, download our guide ›

The Therapeutic Value of a Good Pain Assessment ›

A story for healthcare professionals

Managing pain and other symptoms concurrently

CancerChoices Senior Clinical Consultant Laura Pole, MSN, RN, OCNS, Palliative Care Educator/Consultant: Those of us involved in helping people with cancer manage their pain have long witnessed a connection between cancer-related pain and other symptoms. Usually, what we see is that if someone’s pain is poorly managed, especially for a long time, they feel more anxious, depressed, and fatigued. They don’t sleep well. Their physical function declines. They see their quality of life as poor. In turn, these other symptoms and problems worsen their perception of pain.51Thielking PD. Cancer pain and anxiety. Current Pain and Headache Reports. 2003 Aug;7(4):249-61.

This becomes a vicious cycle. It’s imperative to directly treat the pain with effective pain management therapies—with this, the other related symptoms often improve. Though it’s also helpful to manage other symptoms that are linked to the pain, this should be in addition to, not in place of, pain treatments.52Cleeland CS. The impact of pain on the patient with cancer. Cancer. 1984 Dec 1;54(11 Suppl):2635-41; Thielking PD. Cancer pain and anxiety. Current Pain and Headache Reports. 2003 Aug;7(4):249-61.

Opioids for cancer pain management: fears about prescribing

CancerChoices Senior Clinical Consultant Laura Pole, MSN, RN, OCNS, Palliative Care Educator/Consultant: Every knowledgeable clinician caring for people with cancer pain knows that opioids are often necessary in treating moderate to severe persistent cancer-related pain. And most likely, if you prescribe opioids, you’re aware of the increasing scrutiny and restrictions as a backlash of the prescription and illicit drug abuse that has become known as the opioid epidemic.

A 2021 study found a dramatic decrease in opioid access among terminally ill cancer patients over a recent 10-year period. The authors link this worsening of end-of-life pain management to heightened opioid regulations.53Enzinger AC, Ghosh K et al. US trends in opioid access among patients with poor prognosis cancer near the end-of-life. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2021 Sep 10;39(26):2948-2958. An excellent article in the Journal of Oncology Practice provides much needed perspective and guidance on balancing public health concerns, patient needs, and prescription oversight.54Page R, Blanchard E. Opioids and cancer pain: patients’ needs and access challenges. Journal of Oncology Practice. 2019;15:5:229-231.

To read the full commentary on this issue, including more recent practices being adopted by palliative care specialists, download our guide ›

Helpful links for professionals

Learn more

References